Part III

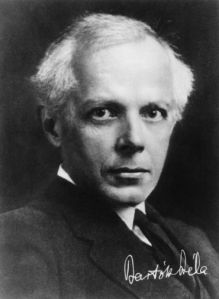

Another fundamental cycle of music of the string quartet repertoire is the set of six quartets by Béla Bartók (1881-1945). Like the collection of Beethoven quartets, Bartók’s cycle spans the length of his compositional career. Bartók developed in his music a very personal and individual solution to the chromatic crisis that was early twentieth century music. Like our pal Ludwig, Bartók was an accomplished concert pianist, as well as composer. Béla Bartók also was one of the earliest persons to study, record, and describe folk music. In doing so, he became one of the founding academic authorities on ethnomusicology. I absolutely adore and identify with all of the music of Béla Bartók, and have for many years (as my musical brother Mike could attest to).

As chromatic and hyper-organized as Bartók’s music is, it almost always has a tonal center. He is not a completely atonal composer in the sense of Schoenberg or Webern. His fascination with mathematics and symmetry is evident in the way he incorporates The Golden Ration and the Fibonacci Sequence into many of his compositions. The chromatic harmonic language of his works is often derived from whole-tone, octatonic, and other non-traditional scales (sometimes borrowed directly from his folk music research). Small intervallic cells of notes become fundamental structural elements connecting themes and entire movements with one another. The Bartók specialist Ernő Lendvai wrote a revealing 115 page volume describing many of these organizing features of some of Bartók’s music. (Béla Bartók, An Analysis of his Music)

As chromatic and hyper-organized as Bartók’s music is, it almost always has a tonal center. He is not a completely atonal composer in the sense of Schoenberg or Webern. His fascination with mathematics and symmetry is evident in the way he incorporates The Golden Ration and the Fibonacci Sequence into many of his compositions. The chromatic harmonic language of his works is often derived from whole-tone, octatonic, and other non-traditional scales (sometimes borrowed directly from his folk music research). Small intervallic cells of notes become fundamental structural elements connecting themes and entire movements with one another. The Bartók specialist Ernő Lendvai wrote a revealing 115 page volume describing many of these organizing features of some of Bartók’s music. (Béla Bartók, An Analysis of his Music)

In true OCD fashion, the best place for me to start a discussion of the Bartók quartets is with his String Quartet Number 1, Opus 7 in A minor. The first edition of the work was published with the title “ Vonósnégyes”, which is simply Hungarian for “First String Quartet”. I am not entirely sure why this title was removed in subsequent editions of the score. One should not put too much emphasis on the “A minor” indication in the title. While it is true that many of the structural points of the quartet center on some harmony built on the note “A”, this is a highly chromatic work that does not use an A minor scale as its foundation. The opening of the first movement is a wonderfully constructed slow fugal section, starting with the violins, who are then joined by the viola and cello seven bars later. This opening has reminded some listeners of Beethoven’s Quartet in c sharp minor, Opus 131, which also opens with a slow fugue. Bartók was surely aware of the late Beethoven quartets when he put a pen to paper to start his own.

These opening melodic figures become structural elements of all three of the quartet’s movements. There is an interesting story behind the opening melody. At some point in 1906 or 1907, Bartók fell passionately in love with a young violinist named Stefi Geyer. She was a talented musician, and the two exchanged many long letters. Clearly, the most personal thing a composer can do for a violinist he loves, is write a concerto for her, which is what Bartók did. Unfortunately, this was one of the many unsettled times in Béla Bartók’s life. He was raised a Roman Catholic, but at this point in time had lost faith and declared himself an atheist. As one can expect, this is not a peaceful serene sort of declaration. Bartók wrote long tirades in his letters to Geyer against Roman Catholicism, and also the middle class. (I’m not sure what Béla had against the middle class). Stefi Geyer must have found all of this a bit of a turn off, because the relationship did not work out. Bartók took the violin concerto he wrote and put it in a drawer. It was never played until after his death. What he then did was use a melody from that concerto for the opening motif of his First String Quartet. In a letter to Geyer he described the first movement of the quartet as a “funeral dirge”. The entire work is built on elements from this opening motive. In this sense, Bartók’s First String Quartet is a masterpiece of a breakup letter. Not bad if you ask me; I was lucky to get half of my record albums back after any of my breakups.

Less than a year later, the 28 year old Bartók married the 16 year old Márta Ziegler, in a marriage that lasted 15 years before they divorced. About two months after the divorce, the 42 year old Bartók married a 19 year old Ditta Pásztory, who was a piano student that he proposed to just 10 days before. I suppose we can draw two conclusions from this, that Béla Bartók did not like to be alone, and he did have an attraction to younger women.

Many string quartet ensembles have made a project of recording all six of Béla Bartók’s quartets. There are quite a few marvelous modern recordings from which to choose. The video below is from the fine cycle done by the Takács Quartet, an Hungarian group now based in Colorado. I think they have a very personal affinity for the music of their fellow Hungarian, and I hope you enjoy their performance as much as I do.

Béla Bartók – String Quartet No. 1 in A minor – Takács Quartet

This is lovely, what a sweet, sad story.

very nice piece